Written in January 2018

I have Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

My Beginnings

I grew up on the Gold Coast, Queensland. My upbringing was full of love and my school-life rich and busy. Looking back, I would describe myself as a textbook overachiever; school captain, tennis team captain, debating team captain, chosen for young leader development programs, section leader and concertmaster (saxophone) of all the school bands, to name just a few. I was everything you might imagine a 17-year-old teenage boy would be; bright-eyed, energetic, optimistic, ambitious, materialistic, naive and the life of the party.

In September 2009, I graduated from Bond University with an undergraduate Business Law Degree. At the age of 20, I didn’t know much about the world, but I did know enough by then to realise that I didn’t want to be a Solicitor or join the proverbial hamster wheel and climb the corporate ladder. I had a solid grasp of the judicial system and was well practised in interpreting legislation and presenting evidence in a court setting. I was also young, energetic and considered myself to be quite fit and healthy.

Having just graduated from a degree that it seemed increasingly likely I wasn’t going to put to use, I assessed my career options for ways in which I could put my legal background and youthful exuberance to good use. At the time there seemed to be only one obvious choice, and that was to become a Queensland Police Officer.

The Queensland Police Service Academy

In February 2010, I began my journey to becoming a Police Officer at the Queensland Police Service Academy at Oxley. During this time, I was taught the essential skills of becoming a Police Officer – legislation, policy, firearms, driver training, physical skills and the field training program. On the 27th of August 2010, I marched out of the Academy as a sworn Constable of Police and began my first year of active duty as a First Year Constable, stationed on rotation in the Logan District. Logan was the ultimate training ground.

The Initial Years

My time at Crestmead Police Station, was a baptism by fire into elements of the community I not been exposed to previously. Domestic violence incidents, pursuits of stolen vehicles, armed robberies, murders and street brawls became my bread and butter. I adapted to this highly stressful workload (or so I thought) incredibly well and began to receive recognition and accolades from my peers and the Logan community alike quite early on. 12 months after my initial posting to Crestmead Police Station I became a Field Training Officer and began to mentor First Year Constables and recruits who would visit Crestmead Station on rotation. I thrived under the additional responsibility and took great pleasure in sharing my knowledge and promoting the growth and professional development of other officers who were fresh to wearing the suit of blue.

At about the same time as the experiences at Crestmead Police Station were unfolding, I remember beginning to feel fatigued for the first time. I put it down to the adrenaline dump of high-stress situations and the toll of shift work. I ignored the exhaustion and compensated with sugar and caffeine hits to help get me through each long day or night. Without understanding the emotional and physical debt that was slowly building, I found it difficult to sleep and without the skills to talk about it. I also started to have mood swings, often easily irritated or offended over the slightest inconvenience. As I began to harden myself against the negatives of a job I was so good at, I had no idea that I was starting to unravel.

The Unravelling

It wasn’t until late 2012, when I had returned home from a suicide incident, that I began to experience nightmares. I had been to many suicide incidents before this one and still to this day I’m not sure what made this incident so significant. I won’t go into too much detail here, but needless to say, the death of a 12-year-old boy in Marsden hit me. Hard. I couldn’t sleep and when I did I would have nightmares. I couldn’t be alone with my thoughts because when I was, I experienced flashbacks and hyper-awareness of my surroundings. When I was on shift I would actively avoid patrolling or attending incidents on the same street of where this suicide occurred. This was the beginning of my PTSD journey.

I remained at Crestmead Police Station until 2014. During this time, I attended countless critical incidents where firearms were drawn, murders, suicides, home invasions, domestic violence, fatal traffic crashes and sexual assaults. All types of incidents that resulted in high stress and high adrenaline. A state of heightened conflict became the norm for me. I became addicted to the adrenaline rush of being first on the scene to a ‘hot job’ and all modesty aside, I was good at responding to critical incidents.

Unfortunately, I was not very good at processing these incidents and I carried the emotional load of them with me each day. My moods fluctuated all the time – I was up and down all at a given moment. I was sad, happy, angry and distant. I would hardly ever sleep for fear of nightmares and reliving certain situations. I also cried – a lot. I wasn’t able to understand what was happening to me and at the age of 23, I didn’t have the perspective or experience to understand that something may be wrong.

Police Officers weren’t meant to be flawed or vulnerable, they were strong, resilient individuals who wore a suit of blue Teflon.

I thought that Police Officers shouldn’t be flawed or vulnerable. My perception of Police Officers were that they were strong, resilient individuals who wore a suit of blue Teflon. I could’t reconcile what I was experiencing with what I thought to be true.

I also didn’t want the weight and the gravity of these situations and how I was feeling to affect my amazingly supportive partner Lisa, the result of which ultimately caused a relationship breakdown. And if you ask her, she’ll tell you about the agony of watching this change happen and the struggle to keep me communicating. That’s a whole other blog post. Well before I reached any state of self-awareness, I kept my emotions bottled up and immersed myself in high risk and high-stress situations.

S.O.S.

At the age of 23, I put my hand up for help. I recall asking Senior Officers for assistance as I knew I was struggling. The flashbacks, the nightmares, the hyper-vigilance became too much for me to bare and I couldn’t go through this any longer. When I had these conversations with Senior Officers, I wasn’t greeted with the reception that I had expected. I was told not to submit any official documentation or to reveal my struggle publicly or on the record for fear of what it may do to my reputation and my career prospects. The Officers I chose to confide in knew me well. They knew me as a young and ambitious Officer who had achieved a lot in operational Policing in a relatively short time. Because of this, I was told that if I needed help that I should source professional assistance privately and outside of the Service. Looking back now, after working through some anger, I don’t blame these Officers for their response. I harbour no animosity and place no blame. They were trying to protect me in the best way they knew how. They were working in a broken system that still perpetuated the ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ mentality. They were just looking out for my career and I still have a great deal of respect for each of them. But it leaves me with questions about Police culture, support and safety nets.

The PTSD Diagnosis

In late 2013 I hit rock bottom. I drank to excess, I pushed away those closest to me. I did things I’m not proud of. My relationship broke down.

I was no longer the Teflon Officer. I felt broken.

Looking back, this was my divine moment. I had the choice of letting things get worse and wallowing further into depression and self-destructive behaviours or I could take decisive action and set about rebuilding my life and repairing the relationship damage that I had caused.

It took me a while to gather the courage to seek out professional assistance to help make sense of what I was experiencing. Looking back, I believe the reason it took me so long was a great deal of shame I felt for needing to reach out. I also didn’t want the Police Service to find out that I may have a mental illness for fear of what it would do to my career. It took me until a point of complete overwhelm where I couldn’t think or do anything clearly. At this time, I visited my local GP and asked to be referred to a psychologist – privately. I was fortunate enough to be referred to one of the most esteemed psychologists on the Gold Coast who specialised in mental health and providing Cognitive Behaviour Therapy to emergency service personnel.

Having lived the experience of reaching out for help, the two things I couldn’t recommend higher would be to:

a) start with an appointment with your GP or treating physician AND

b) find a treatment option that works for you and keep trying until you’ve found it.

Whilst talk therapy/Cognitive Behaviour Therapy in combination with exercise worked for me, it’s not the only treatment option available. There are a number of complimenting treatments available. Chat with your GP about what they would recommend and don’t be afraid to try a number of options until you find one that works for you.

I endured 3 months of intensive one on one Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, relaying the primary and secondary exposure to trauma and how they manifested and affected my personal life. During these sessions, the psychologist told me that I had Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. I had a mental illness. Part of me was relieved. Relief that someone finally has listened and that someone was taking my encounters with trauma seriously. I was also overwhelmed, vulnerable and felt a great deal of shame. I felt that I couldn’t let anyone know for that would be weak – the exact opposite of the Teflon officer who is bulletproof and resilient.

I decided to keep this diagnosis confidential for fear of what it would do to my occupation. I did, however, read extensively about what it meant to have PTSD. I tried my best to understand and better my situation and reached out to those I had pushed away. With a great deal of effort, courage, compassion, and love Lisa allowed me back into her life.

The Queensland Police Service Child Protection & Investigation Unit

In early 2014 I applied for and received my dream job – Plain Clothes Investigator with the Logan District Child Protection and Investigation Unit. The Officers in the Logan CPIU are amongst the most professional, diligent and resilient Detectives in the entire Police Service. They are skilled investigators, interviewers, critical thinkers, and innovators. I recall sitting a psychometric assessment prior to being appointed to the Unit. Part of which was disclosing any mental illnesses that I was or had experienced. I omitted the fact that I was suffering from PTSD as I knew I wouldn’t be successful in obtaining a position.

When I received the notification that I was successful in my application I was so proud and grateful to be a part of such an amazing team of investigators. We undertook many protracted and complex investigations of child abuse, instances of child harm and juvenile justice. Serious sexual and physical assaults and extreme cases of neglect became by bread and butter. I acknowledge that I write about these incidents with a degree of distance. It’s still a coping mechanism to distance myself from the emotional load that I carry with each of these incidents.

Leaving the Queensland Police Service

In 2015 I knew I had to leave the Queensland Police Service. I was truly grateful for the opportunity to be a part of the CPIU and contribute towards meaningful outcomes for some of the most vulnerable people in our community. But, despite these outcomes, I was still suffering from PTSD. Lisa had been successful in obtaining a position at Melbourne University to undertake a PhD in Music Composition. It was the opportunity of a lifetime. In August 2015, I made the difficult yet empowering decision to resign from the Queensland Police Service.

When we moved to Melbourne I tried a number of career options including Case Manager and Team Leader for a not for profit child welfare agency and Child Protection Practitioner with the Victorian Government. Nothing felt right and although I thought I was helping to better the lives of others, I was just another cog in the red-tape machine of government policy. I was also experiencing what I labelled a ‘detox’ period from the Police. Part of me was still seeking the thrills, adrenaline and the need to help and serve others that comes from being a frontline Police Officer. I was conflicted with thoughts of wanting to join Victoria Police, but after a considerable amount of soul searching, I knew this would be a detrimental choice to make.

At the same time, I signed up to a local gym and undertook several personal training sessions. I became fitter, stronger and faster than ever before. But the ultimate benefit? With a focus on fitness and overall wellness, my symptoms of PTSD – the flashbacks, the nightmares, the hypervigilance all dramatically decreased. My stress levels and sleep became regular and my relationships were thriving. I found great solace in the profoundly positive correlation between exercise and positive mental health regulation.

Vulnerability Can Equal Strength

To truly own my PTSD journey, I know that I have a personal and public responsibility to raise the profile of PTSD and to empower those who suffer from the debilitating disorder to seek the support of professionals who can help them recover. I have chosen to assist others who may be suffering from PTSD and lead by example by making my story and my journey public. I have chosen to do something which terrifies me, but for all the right reasons.

Up until now, I have been unable to sit for long periods of time in my own thoughts. For it’s in this quiet or reflection that thoughts, feelings, and memories associated with traumatic incidents generally occur. I am terrified at the thought of enduring these nightmares for a sustained period.

So, what am I going to do about it? Well, true to my ‘all or nothing’ personality, I’ve crafted up a scenario that gives me no option but to do exactly what I’ve been avoiding. In late August I will be facing this fear head-on by tackling an ultra-endurance event where I will be forced to sit with my thoughts and negative cognitions associated with my PTSD journey over six self-reliant days. I can only imagine how emotionally confronting this might be, more so than the physical challenges.

Extreme Measures: Passion meets process

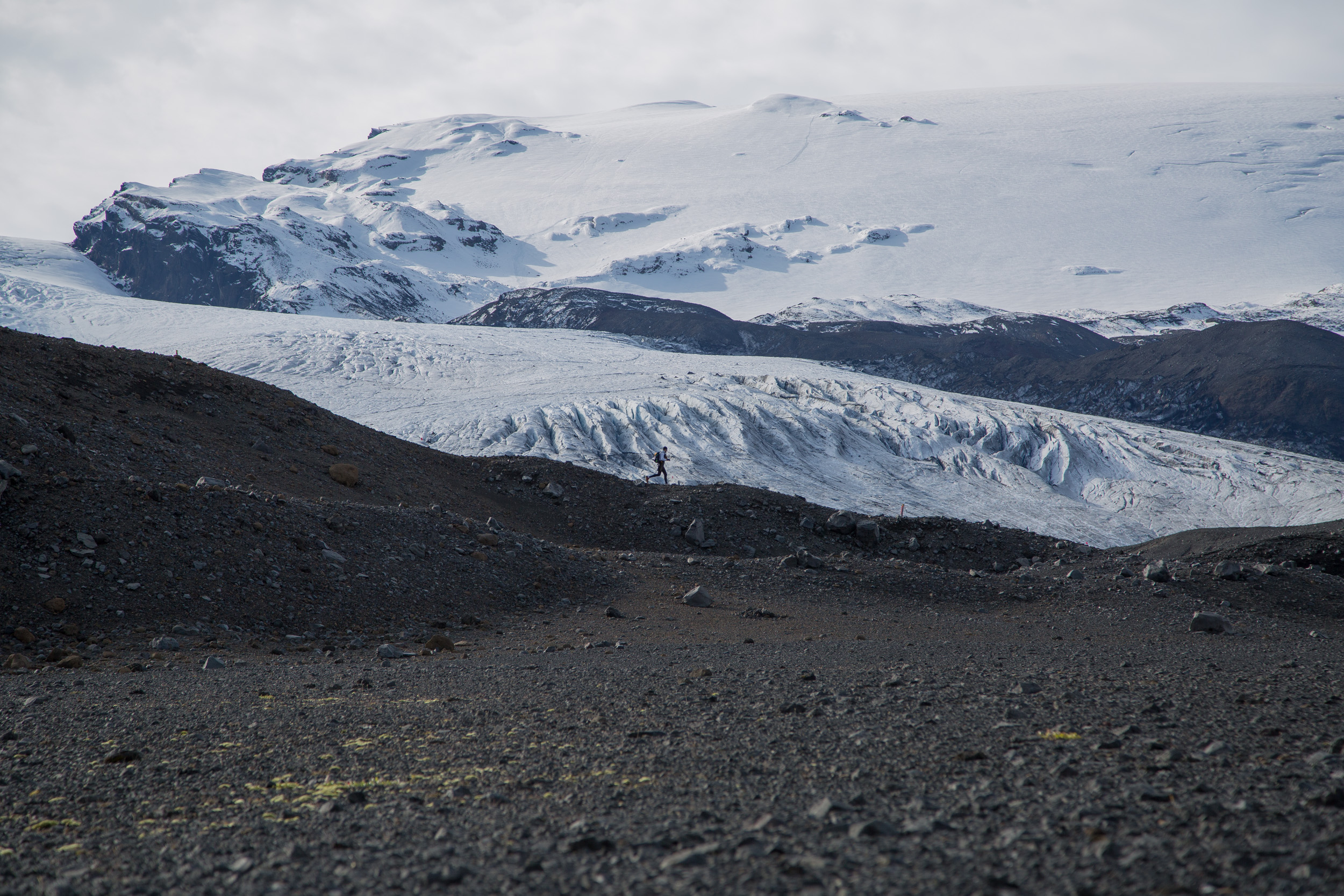

In August 2018, I will be competing in the ‘Fire and Ice Ultra Marathon‘, one of the toughest multi-terrain races in the world, spanning 250 km through undulating terrain situated in the Icelandic Highlands. I will be representing Australia in Iceland, competing against some of the world’s most elite ultra-runners. Whilst training for and competing in this gruelling event I am championing support and raising the awareness of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and the exceptional work conducted by Phoenix Australia – The National Centre for Excellence in Post Traumatic Mental Health.

Fire and Ice looks a little something like this…

My pursuit is to assist in changing the stigma that surrounds mental health, raise the profile of PTSD and to empower those who suffer from the debilitating disorder to seek the support of professionals who can help them recover. No one should suffer from this condition alone – I am racing to bring about change, raise awareness about trauma and PTSD and let others know that there is help available.

In competing in this event, I have the honour of being sponsored and supported by Kathmandu, who are supplying the technical gear and apparel required. I am truly grateful for their support! However, I am still responsible for my own training, travel, race fees, insurance, accommodation and on the ground expenses.

I know this is a big ask in so many ways: emotionally, physically and financially. I’m reaching out to ask for your help. I cannot complete this task without your support.

How To Show Your Support

- If you wish to support my participation in this ultra-marathon you can do so by making a donation through my ‘mycause’ page www.mycause.com.au/page/162984 until 1 August 2018. Funds raised through this platform will help to offset the significant preparation costs in representing Australia on the world stage as I run to raise the profile of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

- Help me in my goal of raising awareness of PTSD and support options and my journey by subscribing to this blog, sharing it with your friends and social media platforms

- Pledge a donation to Phoenix Australia: Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health via my ‘mycause’ page www.mycause.com.au/page/162984 as well. Your support means more than you realise, not only myself but to others who endure Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

2018: Where To From Here?

My next series of blog posts will cover both the physical and mental elements of training for the ultramarathon race (including strength, conditioning, mobility, recovery, mindset and nutrition), as well as my ongoing journey with PTSD. This will include the highs and the lows of relapse (being triggered and re-experiencing primary trauma symptoms), recovery and the residual symptoms associated with the reality of living with PTSD.

Further, in upcoming blogs, I look forward to sharing resources, books, podcasts and publications that are essential to have in all PTSD toolkits. If you’ve read or listened to something that you think is worth including in this list, please reach out – the more the better.

If you or someone you know and love experiences Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, I invite you to get in touch via email or leave a comment below. If you were impacted by this post, I encourage you to contact a service from the list below and reach out for support.

Seeking Help for PTSD

Credit: Black Dog Institute

If your life is in danger call emergency services:

- Australia – 000

- New Zealand – 111

Lifeline Counselling (24 /7)

- Australia – 13 1114

- New Zealand – 0800 543 354

Men’s Line Australia – 1300 78 99 78

Beyond Blue Support Service – 1300 22 4636

Kids Help Line – 1800 55 1800

Suicide call back service – 1300 659 467

You can also: talk to someone you trust, visit a hospital emergency department, contact your GP, a counsellor, psychologist or psychiatrist.

Yours in health,

James